|

"The Recording of Fleetwood Mac's

Rumours"

Memories of the Making of Rumours

Richard Dashut (co-producer):

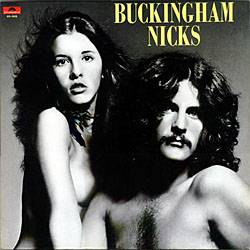

I'd worked with Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks since their debut album,

Buckingham-Nicks. After they joined Fleetwood Mac, Lindsey invited me to do

their live sound. They started recording Rumours in Sausalito, across the bay

from San Fransico, with the Record Plant's engineer, but they fired him after

four days for being too into astrology. I was really just around keeping Lindsey

company, then Mick takes me into the parking lot, puts his arm around my

shoulder and says, Guess what? You're producing the album. The funny thing was,

I never really wanted to be a producer. I brought in a friend from wally

Heider's studio in Los Angeles, Ken Caillat, to help me, and we started

co-producing. Mick gave me and Ken an old Chinese I-Ching coin and said, Good

luck.

Cris Morris (recording assistant):

I'd helped build the Record Plant. I knew every nail, because I'd driven

most of them in. I'd helped make what became known as Sly Stone's Pit, a control

booth sunk into the floor, so the musicians could sit and play around it. When

we recorded Sly there, he had his own personal tank of nitrous oxide installed,

and that was still there.

Mick Fleetwood (Fleetwood Mac):

It was a bizarre place to work, but we didn't really use Sly Stone's pit.

It was usually occupied by people we didn't know, tapping razors on mirrors.

Chris Morris:

Because Record Plant had three studios, a lot of other musicians dropped by.

Van Morrison hung out a lot. Rufus and Chaka Khan, Rick James. Jackson Browne

and Warren Zevon came down because Jackson wanted Lindsey and Stevie to do

backing vocals on his album.

Herbie Worthington (photographer):

I'd been working with them since 1974, so when they started Rumours, I was

brought in to document it for the inner sleeve. The girls were kind of kept

apart, in a hotel while I lived with the guys in a house that belonged to Record

Plant, about five minutes away. Things personally, were falling apart for them.

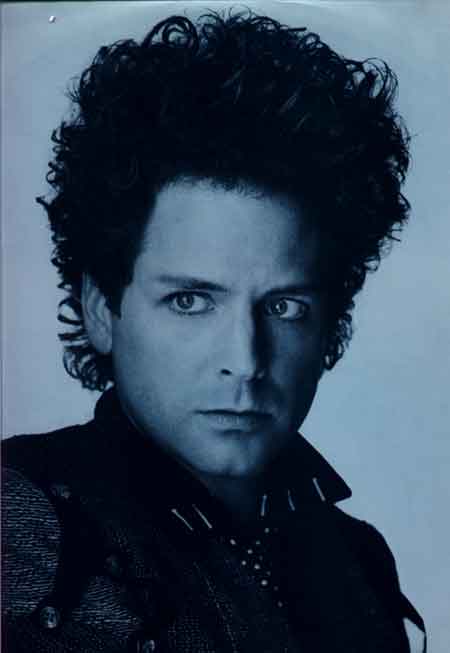

Lindsey Buckingham (Fleetwood Mac):

You had both couples, John and Christine McVie and Stevie and myself, in the

process of breaking up during the making of the album, so you had all this

cross-dialogue going on in the songs.

Christine McVie (Fleetwood Mac):

We had two alternatives - go our own ways and see the band collapse, or grit

our teeth and carry on playing with each other. Normally, when couples split,

they don't have to see each other again. We were forced to get over those

differences.

Herbie Worthington:

Mick was like the father hen, always overseeing everything, although his

marriage to Jenny Boyd was breaking up too. He wanted everybody to be so happy

so the atmosphere would be creative. For example, he would take the clocks out

of the studio so people were less aware of time passing.

Chris Morris:

Mick also co-owned Fleetwood Mac with John. Lindsey and Stevie were just

hired to play with the band. Now, John's ideas were rooted in blues and that

didn't get with Lindsey who was more pop and experimental, which caused extra

friction. Mick being the boss, sided with John.

Richard Dashut:

It took two months for everyone to adjust to one another. Defenses were

wearing thin and they were quick to open their feelings. Instead of going to

friends to talk it out, their feelings were vented through their music: the

album was about the only thing they had left.

Lindsey Buckingham:

There was nothing specifically worked out when we went in the studio. We

didn't have demo takes. The whole thing just happened.

Christine McVie:

When we went in, I thought I was drying up. I was practically panicking

because every time I sat down at a piano, nothing came out. Then one day in

Sausalito, I just sat down and wrote in the studio, and the four and a half

songs of mine on the album are a result of that.

Mick Fleetwood:

We started trying to put down basic backing tracks, although we were all

feeling so desperately unhappy with life. We spoke to each other in clipped,

civil tones, while sitting in small airless studios, listening to each other's

songs about our shattered relationships.

Herbie Worthington:

One night in the control room, John came in with a bottle of wine. I was

photographing the girls, but he grabbed some cord and stuck it into the neck of

the bottle. Then he turned it upside down, taped it once on the floor with the

other end of the cord taped to his arm, so it looked like he was getting an

intravenous drip of alcohol. We were cracking up, but it was very symbolic of

everything that was going on.

Mick Fleetwood:

It was the craziest period of our lives. We went four or five weeks without

sleep, doing a lot of drugs. I'm talking about cocaine in such quantities that,

at one point, I thought I was really going insane.

Chris Morris:

Meanwhile, we were trying to get unique sounds on every instrument. We spent

ten hours on a kick drum sound in Studio B. Eventually, we moved into Studio A

and built a special platform for the drums, which got them sounding the way we

wanted.

Christine McVie:

Dreams developed in a bizarre way. When Stevie first played it for me on the

piano, it was just three chords and one note in the left hand. I thought, This

is really boring, but the Lindsey genius came into play and he fashioned three

sections out of identical chords, making each section sound completely

different. He created the impression that there's a thread running through the

whole thing.

Chris Morris:

Never Going Back Again, which we did in Sound City in LA, took forever. It

was Lindsey's pet project, just two guitar tracks but he did it over and over

again. In the end his vocal didn't quite match the guitar tracks so we had to

slow them down a little.

John McVie (Fleetwood Mac):

It was very clumsy sometimes. I'd be sitting there in the studio while they

were mixing Don't Stop, and I'd listen to the words which were mostly about me,

and I'd get a lump in my throat. I'd turn around and the writer's sitting right

there.

Chris Morris:

For that one, I sat between Mick and Christine because her piano was set up

so that she was at an angle to his drums and they couldn't see each other, but

hey could both see me. I had to stand there for six hours co-ordinating the

time.

Mick Fleetwood:

Go Your Own Way's rhythm was a tom-tom structure that Lindsey demoed by

hitting kleenex boxes or something. I never quite got to grips with what he

wanted, so the end result was a mutated interpretation. It became a major part

of the song, a completely back-to-front approach that came, I'm ashamed to say,

from capitalising on my own ineptness. There was some conflict about the "crackin'

up, shackin' up" line, which Stevie felt was unfair, but Lindsey felt

strongly about. It was basically, "On your bike, girl!"

Christine McVie:

The Chain started as the tail end of a jam and we did it all the wrong way

around. We kept the end bit and added a new beginning. We used Stevie's lyrics,

I created the chorus and Lindsey did the verses. I really don't know how it all

came together.

Richard Dashut:

The only two instruments that were actually played together on that album

was the guitar solo and drum track on The Chain. It wasn't necessary or even

expedient for them all to be in the studio at once. Virtually every track is

either an overdub, or lifted from a separate take of that particular song. What

you hear is the best pieces assembled, a true aural collage. Lindsey and I did

most of the production. That's not to take anything away from Ken or the others

in the band - they were all involved. But Lindsey and myself really produced

that record and he should've gotten the individual credit for it, instead of the

whole band.

Chris Morris:

Somebody, one of Lindsey's girlfriends I think it was, came in one night

with some marijuana cookies - we called them the thousand dollar cookies. They

turned out to be incredibly powerful and everybody got very zonked out for the

next twelve hours. We lost the rest of that day and most of the one after.

Mick Fleetwood:

Things got so tense that I remember sleeping under the soundboard on night

because I felt it was the only safe place to be. Eventually the amount of

cocaine began to do damage. You'd do what you thought was your best work, and

then come back next day and it would sound terrible, so you'd rip it all apart

and start again.

Chris Morris:

Recording Gold Dust Woman was one of the great moments because Stevie was

very passionate about getting that vocal right. It seemed like it was directed

straight at Lindsey and she was letting it all out. She worked right through the

night on it, and finally did it after loads of takes. The wailing, the animal

sounds and the breaking glass were all added later. Five or six months into it,

once John had got his parts down, Lindsey spent weeks in the studio adding

guitar parts, and that's what really gave the album its texture.

Richard Dashut:

We wore out our original 24-track master. We figured we had 3,000 hours on

it and we were losing high end, transients and much of the clarity. The drums

were valid and maybe a couple of guitar parts. We ended up transferring all the

overdubs on the master to a safety master. We had no sync pulse to lock the two

machines together, so we had to manually sync the two machines - ten tracks by

ear using headphones in twelve-hour sessions. People thought we were craze but

it turned out really good.

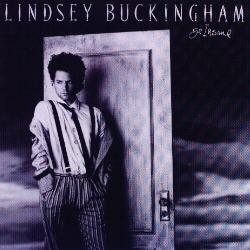

back to

Lindsey in-print

|