Guitarist, studio craftsman, singer and

tunesmlth, Lindsey Buckingham has emerged

from the shadows of megapop's Big Mac as a creative force and stage presence.

Herein he discusses the group's change In direction, Its musical relationships, and

his view of the recording process

Summer, 1976

More than 60,000 file into the Oakland Coliseum's outdoor stadium for a "Day On The Green"

featuring Peter Frampton, Gary Wright, and Fleetwood Mac. Bill Graham is billing the

concert as the British invasion, although two-fifths of one of the acts grew up in

California. Guitarist Lindsey Buckingham, 27, was in fact born in Palo Alto, about thirty miles from the

Coliseum, where he is now playing as part of Fleetwood Mac. In a white peasant shirt, beard and curly hair, Buckingham

looks decidedly California. Since the vast majority of the sun worshippers have come to

hear Frampton sing "Show Me The Way," Fleetwood plays a rather abbreviated set, only partially culled from their latest,

self-titled album. Midway through the program, Buckingham, who has remained in the background for most of the set,

comes to the microphone. "We'd like to do a Peter Green song for you now," he says, almost

self-consciously, before breaking into the band's 1970 hit, "Oh Well," written and

originally sung by the group's founder.

February, 1977

Fleetwood Mac kicks off their 1977 tour with a benefit for the Jacques Cousteau Society at the Berkeley Community

Theater. Except for a short film about penguins (long a symbol of Fleetwood Mac), the band is the only act on the bill. Material

from their just-released Rumours LP is met with as much applause of recognition as songs from their previous album,

which garnered three hit singles. Midway through the show it becomes apparent that vocalist

Stevie Nicks, battling a strained throat, is not going to be able to make it through the set. The spotlight turns to the band's

other two songwriters, Christine McVie and, more noticeably, Lindsey Buckingham, who displays a degree of confidence

and guitar technique barely hinted at on album. The concert climaxes near the end with Buckingham's dramatic

"I'm So Afraid," taken a bit slower than the recorded version.

December, 1979

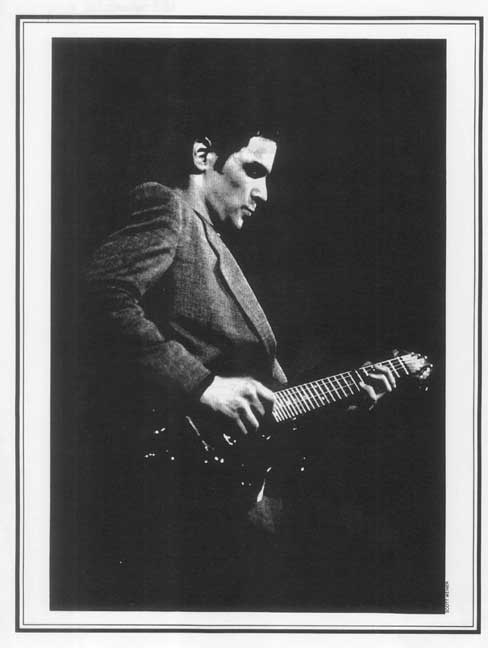

Dressed in a black shirt and a plain gray suit, his hair cropped short, Lindsey Buckingham is pacing the stage of

San Francisco's Cow Palace. The guitarist clearly stands out from the rest of the band, both musically and visually. Whether

he is singing one of his own songs from the new Tusk album or backing Nicks or McVie on one of their tunes, Buckingham

plays and looks like a man possesed -- his fixed stare never leaving the audience, a sinister grin never leaving his face.

With three rim shots from Fleetwood's snare drum and a piano glissando from Christine McVie, Buckingham shouts,

"What makes you think you're the one," pointing at his ex-girlfriend Stevie Nicks. As has come to be expected, the set's

highpoint is "I'm So Afraid," a tour de force study in dynamics with Lindsey Buckingham's echoing guitar building in speed,

volume and intensity.

In its fifteen years as a band, Fleetwood Mac has undergone

more changes than any group from the Sixties that is still intact. Starting out as an English homage to Chicago blues,

they have survived underground cult status to become one of the most popular groups in pop music today. They have

endured what seems like one personnel change per album, especially in the guitar department, which has seen Peter

Green, Jeremy Spencer, Danny Kirwan, and Bob Welch come and go. Bassist John McVie and drummer Mick Fleetwood are

the band's only remaining original members. In the past six years Fleetwood Mac's personnel has

remained constant, if not necessarily stable, with Fleetwood, McVie, vocalist Stevie Nicks, McVie's ex-wife Christine on

piano, and guitarist Lindsey Buckingham, who has individually gone through nearly as many changes as the

band has collectively.

Buckingham was born in 1949 and took up guitar at seven, strumming along to his older brother's collection of Elvis

Presley, Buddy Holly and Everly Brothers records. He later turned to folk music (the Kingston Trio, lan and Sylvia, John Herald),

studying banjo and fingerpicking styles. In the late Sixties he played electric bass in a Bay Area rock band called Fritz,

which featured vocalist Stephanie Nicks. When Fritz broke up, Lindsey and Stevie stayed together, both musically and

romantically, and recorded one album for Polydor, Buckingham Nicks, produced and engineered by Keith Olsen (with an

assist from Richard Dashut).

In December of 1974, Mick Fleetwood was looking for a studio at which to record Fleetwood Mac's next album and

came to Sound City in Los Angeles where Keith Olsen played him a track from Buckingham Nicks, "Frozen Love." Two

weeks later guitarist Bob Welch announced that he was leaving Fleetwood. On New Year's Eye the drummer telephoned

Olsen to ask about the pair he'd heard on the record Olsen had played him. As it turned out Buckingham and Nicks were there

at a party at Olsen's house. Without so much as an audition Fleetwood offered them both a

job with the band.

Fleetwood Mac was recorded early in 1975 and gave the

band an element that had previously been missing -- catchy, welt-crafted hit singles. "Over My Head," "Rhiannon," "Say

You Love Me" -- virtually every cut on the LP probably could have become a hit single, but the band had the good sense

and taste to stop after three or four and record a follow-up album.

Rumours was recorded in 1976 amid tensions that saw the McVie's divorce and Lindsey and Stevie split. When the album

was released in 1977, Fleetwood Mac found themselves almost simultaneously on the covers of Rolfing Stone and

People Magazine. Rumours spun off as many hits as the previous album -- "Go Your Own Way," "Dreams," "Don't

Stop" -- and became one of the biggest selling albums in pop

music history.

Tusk, the group's quirky follow-up, sacrificed cohesion at the

expense of a few million in record sales. Less a group effort than the previous LPs, it has repeatedly been compared to the

Beatle's White Album -- Nicks doing her songs with instrumental backing from the other members, McVie doing her

numbers, very little harmonizing, Buckingham recording several tracks by himself at a makeshift home studio. But, while it

may not hold together well as a unified album, the individual performances on Tusk are nevertheless outstanding,

especially Buckingham's which display a startling new approach to recording

structure, mix and instrumentation.

Last December, after a solid year of touring, than band released it's first Live

LP, Fleetwood Mac Live, before taking five months off from touring and

recoding. They are scheduled to go back into the studio in May to begin work on

their next album.

The reasons for Fleetwood Mac's

ascent to the top are hard to pinpoint, Chemistry is often a word that's batted

about. Having three singer / songwriters the caliber of Buckingham, Nicks and

McVie certainly doesn't hurt. But there is obliviously a

whole-is-greater-then-the-sum-of-the-parts element at work when the band is

really on.

On guitar, Lindsey is as unorthodox as he is underrated. Still basically

employing the techniques he learned on banjo and fingerstyle folk guitar, he

sort of frails and flails his way through solos, often ending the night by bandaging

bloodied fingertips. Buckingham will probably never place at the top of Guitar

Player Magazine's reader poll as Best Rock Guitarist, but a more tasteful lead guitarist would be hard to find. In the words

of John Stewart, "He knows the magic of one note."

Because of his innovative work on Tusk, Buckingham has

become a much sought after producer, although he turns down far more offers than he takes on. He produced Walter

Egan's Not Shy album and Bombs Away Dream Babies for one of his early influences, John Stewart, who regards

Buckingham as "the only genius I've ever worked with in the studio." The former one-third of the Kingston Trio recounts,

"Lindsey came down when we were doing the mix, and he was turning all the pots, layering the guitars. I was watching him

and I said, 'Lindsey, some time you've got to tell me what you're doing.' He said, 'I'm turning the knobs till it sounds right.'

A few people I know of really know how to make that mystical 'thing' happen with a record. Brian Wilson is one;

Lindsey Buckingham is the master at it." (Ironically, Stewart, an acoustic folkie for twenty years, began playing electric lead guitar by

listening to Lindsey's work before discovering that Buckingham had in fact learned to

play acoustic guitar listening to Stewart's records with the Kingston Trio. "1 got the

Fleetwood Mac album," Stewart recalls, "and something about it sure sounded familiar." The one-note solo on Bomb's Away's top

ten single "Gold," while it is one of the best examples of the "Lindsey Buckingham guitar style," was actually played by

Stewart.)

Onstage, perhaps even more so than in the studio, Lindsey Buckingham has become the clear leader of Fleetwood Mac.

In six years he has evolved from guitarist to creative force to kinetic focal point. Even New Wavers, ready to poo-poo

anything by a band that produced such soft-core rock as "Dreams" and "Over My Head," regard Buckingham as a

force to be reckoned with.

While the other four members of the band have been

splashed across every phase of the media, Buckingham has remained somewhat mysterious, in the shadows. As he points

out in the following interview, he seldom gets fan mail and can walk down the street completely unnoticed. "Whatever

appreciation is being offered towards me now," he states, "is the kind of appreciation that I would like to get. It's more from a

musicianship standpoint, hopefully -- it's more fundamental.., it's been honest -- that's for sure,"

MUSICIAN; Going from total obscurity to the top of the charts is what most struggling musicians hope and pray for every day

of their lives. But have there been any drawbacks to that level of People Magazine stardom?

BUCKINGHAM: Well, you see, I don't feel like I've been in the limelight as far as the attention focused on the group. Stevie, in

the beginning, her visual presence and just her personality were so strong. That was always the figurehead of the group,

and still is, in a way. In that way, I really haven't had to deal with a barrage of external adulation by any means. I very seldom

get a fan letter.

MUSICIAN: Can you walk down the street and not be recognized?

BUCKINGHAM: Exactly. Oh yes I can walk anywhere and no one cares. Also,

I'm always changing my hair so that helps.

MUSICIAN: Most people, when they think of Fleetwood Mac, probably still have an image of Stevie Nicks in a top hat and cape. But onstage your position seems to have evolved from being more or less a member of the rhythm section to being the focal point of the band, especially on the Tusk Tour.

BUCKINGHAM: It's certainly working that way; I don't know if that's good or bad. It really can't be helped. But whatever appreciation is being offered towards me now is the kind of appreciation that I would like to get. It's more from a musicianship standpoint, hopefully it's from people who appreciate serious things about music. It has nothing to do with costumes or even image - it's more fundamental. It's nice to open a Rolling Stone and see that you have the big picture for a change, but even so, the whole external aspect of teh success hasn't really gotten through. I don't feel that it's changed me, because it hasn't barraged me very much at all. It's been slow. It's been honest - that's for sure.

MUSICIAN: Has your growth within the group corresponded

with you growing in confidence? Did you feel like you had to try and fit in when you first joined, and now you can do what you

want to do?

BUCKINGHAM: Yeah. It's been very much a series of situations, of having to adapt. The kind of role that, say, Stevie and I

had towards each other and that I had in Buckingham Nicks as compared to what happened six months after we joined

Fleetwood Mac -- I really had to turn around. It was a very good thing to happen. I gained so much more appreciation for

Stevie that way. I had to reevaluate the whole thing. There's been a lot of adapting to do. When I first joined the group, I had

to go and play Bob Welch's songs and all this strange stuff that had nothing to do with me or me growing as an individual. But

that was all part of it; I needed to do that one way or another. Once Stevie and I had broken up and had sort of gotten

through that, it was just a question of seeing what I really had to offer and trying to establish that, and saying, "Hey, I do have

more to offer than just being part of the rhythm section." Also, people don't see what you contribute in the studio, and you

can't expect them to. That's one thing that's always been visible to people very close to me, but never to anyone else.

MUSICIAN: Was the change from Rumours to Tusk a conscious attempt to not get pegged as a pop song group?

BUCKINGHAM: Well, it's really hard to say. In a way, yes. Speaking for myself, my songs are probably more of a

departure than Stevie's or Christine's, but even theirs, the arrangements are slightly different. There's been little effort made to fit

them into a single mold, whereas on Rumours every song was more or less crafted as that kind of song. It's not that the songs

on Tusk are long; in fact, someone asked me when the album

first came out why all my songs were so short. I just said, "Well, rock 'n' roll songs were traditionally short songs." But, for me, it

was a question of experimenting with a new format in recording. Some of those tunes were recorded in my house on my

24-track. The overall atmosphere of the album just evolved by itself. We wanted to do a double album -- I don't think we knew

exactly where it was going. But I was interested in pursuing some things that were a little bit rawer. You just hear so much

stuff on the radio that has the particular drum sound. I mean, everything is worked around the drums these days. It's all so

studio-ized; I thought it was important to delve into some things that were off to the side a little bit more, so that we're not

so clich�d. And we certainly did that -- at the expense of selling a few records. Between the Fleetwood Mac album and Rumours we changed the people we were working with totally,

even though Fleetwood Mac had sold two and a half or three million copies. We could have stuck with a good sure thing,

and we went through a lot of hell reestablishing a working relationship with other people to move forward and to try to

grow, which we did on the Rumours LP. Now on Tusk we more or less did the same thing and took a lot of chances, but we did

it because it was something we felt was right to do and was important, and it shook things up. It certainly shook people's

preconception of us up a bit. We divided our audience a little bit. A lot of people who were sort of on one side and saw Rumours as kind of MOR were really pleased by Tusk; and a lot of people were very disappointed, because they were

expecting more of the same thing. You can't let what you think is going to sell dictate over what you think is important.

MUSICIAN: What sort of music were you listening to that might have influenced the outcome of Tusk?

BUCKINGHAM: Not that much of anything, specifically. The fact the New Wave stuff was emerging helped to solidify or to

clarify feelings or give one a little more courage to go out and try something a little more daring.

But as far as the actual way the songs turned out, it wasn't a question of listening to a

certain group and trying to emulate them at all. No one in particular; the whole scene just seemed so healthy to me. The

stuff on the album isn't that weird to me, but I guess it is for someone who's expecting "You Make Loving Fun" or

something. I was surprised, because I was at that time, and still am, ready to hear some things that I felt were fresh and I thought

were approached slightly differently, in the spirit of the old rock n' roll but contemporary as well. The LP sold about four million

albums -- nothing to cry about. It was interesting to see the reaction. Most of the critical

response to the album was real good, and then some of it wasn't at all. But we definitely divided

our audience,

MUSICIAN: When you write songs, do you make a complete demo tape of it and play it for the band?

BUCKINGHAM: Yes. Now I make masters, though. I've got a 24-track. There are two or three songs on Tusk that were done

that way, just at my house, and they went onto the album.

MUSICIAN: With you playing all of the instruments?

BUCKINGHAM: Yeah. "The Ledge," "Save Me A Place," and "That's Enough For Me."

MUSICIAN: Do you still think of those as "Fleetwood Mac songs"?

BUCKINGHAM: Well, I'm not sure they see them as Fleetwood Mac songs [laughs]. I don't see why they can't be. I think

of them as Fleetwood Mac songs -- we've done some of them live. We ran down "The Ledge" a whole bunch of times and

almost started doing that in the set; we were doing "That's Enough For Me" live. But we had a lot of problems trying to

integrate the stuff from Tusk with the old set.

MUSICIAN: Do your songs come out differently if you work alone as opposed to working them out with the band

members?

BUCKINGHAM: I think we're starting to do that more. One of the things that was exciting about doing Tusk is that we can

take some of that and reapply it to a collective thing a little more than we did on Tusk. Certainly in terms of a group there's

a desire to do that, especially after experimenting with some- thing that was less of a cooperative venture. I think the next

Fleetwood Mac studio album will be more group orientated - it certainly wont be

less. It's not like it's moving in one direction or the other: it's just

expanding and contracting.

MUSICIAN: Do you think you'll ever record a solo album?

BUCKINGHAM: Sure, why not? I don't think there's any stigma to it, other then misunderstanding from the external world. If it makes you fell good. I don't see why not. But I'm not in any great hurry to do my solo album.

MUSICIAN: Would you see a solo project as an outlet to experiment more or just a chance to put more of your own songs on a LP?

BUCKINGHAM: Some of both, I would say.

It wouldn't be radically different - it couldn't get much more different then Tusk. See, one of the things about being in Fleetwood Mac is that Christine writes

pretty much soft, pretty songs, and Stevie more or less does the same thing too.

They both write rock'n'roll songs from time to time, and do it very well, but

the burden of the real gutsiness usually is on me. So if Christine has X amount

of songs, and Stevie has X amount of songs, my slot must almost out of necessity

be pretty tough kind stuff. I think it would be a lot of fun to just experience making a

statement in a broader range of things. If you took all of my

songs from Tusk, they would probably make a more cohesive album than the whole Tusk album, just in terms of cohesion. I wouldn't want to get too much more fringey than something

like "The Ledge," you know. The funny thing is, so many people reacted to that song like, "My God, what is that?" It

didn't even seem that radical to me. See, I'm trying to learn more about writing.

MUSICIAN; Has the creative process of how a song takes shape changed much from Buckingham Nicks to Tusk?

BUCKINGHAM: I'd say it's come back around full circle, in a way, except with a whole lot more knowledge, I would hope.

I've learned so much from John and Mick.

MUSICIAN: In terms of what, since they don't write songs?

BUCKINGHAM: In terms of musical sense. Mick's musical sense is hard to pin down, because it's just such an instinctive

thing. But in terms of just writing songs, that hasn't changed, no. For instance, Stevie will write her words, and everything will

be central to that. That's good; sometimes I wish I could do that. Mine are usually central to a groove of some sort, and

everything else will follow. That hasn't changed over all this time. A lot of rock 'n' rollers do that.

MUSICIAN: Does that method make your songs more traditionally structured than Stevie's?

BUCKINGHAM: They can be, yeah. Which isn't necessarily good. There's a fine line. You take someone like

Springsteen, who has the best of both, I think, in terms of being a writer and someone who knows what he's doing. His phrasing can go

from a certain timing in one line, and in the next line it'll be totally different, because the words are different. Whereas if I

was thinking of those two lines in a song, I might just think of repeating the same thing over and over, because I would still

be sort of nebulous in my mind. I wouldn't have the words completely formed. So there's an advantage by far in being

able to do that, because it gives the whole feeling of the song a certain spontaneity. He's feeling the words in a certain way,

and he's putting them down, and everything else will follow that. Stevie does the same thing with her words; she surprises

you with phrasings. But there's an advantage to the other way, too. If you can eventually get around that, and make it so that

your vocal doesn't sound stiff, then the advantage is that you're so much more aware of how to make one track sound

totally different from the other, in terms of applying a certain instrument to it or something. But in terms of a structure -- like

A-B-A-B-C or whatever -- my songs are probably a lot more that way than Stevie's, because she doesn't really know A-B-A-B-C. She writes like Mick drums.

MUSICIAN: Are your recording and producing techniques pretty much intuitive?

BUCKINGHAM: More or less. This is the first time I've had a real setup. Doing Tusk I had a 24-track little MCI board that l

was working on. Now I've got a Studer 24-track which the band bought quite some time ago. It's a

full-size console and gives me something to work with -- some limiter's, some EQ,

some big speakers, some real equipment. For the first time I'll be able to realize or not realize some of the things that I've felt I

could do. It's very frustrating sometimes in the studio, because you've got so many people in there, and technically I'm not

there to twist knobs or anything. A lot of times you feel you could do a better job than somebody else, because you have

the intuition and they really don't. They've had a few years technical experience, but they can't make the connection

from feeling the song to this, to this, and do it all the way a painter paints, where suddenly all the intuition takes over and

you're just there doing it. That can be what it's like, and I think it offers a lot more opportunity for very unusual things to happen.

Things present themselves, and if you have the intuition to pick them up when they present themselves

and not let them go by, you can get some very unusual sounds. I feel real good about my capabilities as an engineer.

MUSICIAN: Do you think trained engineers, in their pursuit to make something sound neat and clean, can

destroy the emotion?

BUCKINGHAM: All the time. The idea is to capture, the moment that you perceive

something to be a certain way and pursue it right then. Try to pursue thing's that you can hear

in your head to their ultimate disaster or whatever.

MUSICIAN: Do you plan on doing more outside production work with other artists?

BUCKINGHAM: A few people have wanted me !o produce them lately, and it's nice to know that people want you to work

with them, but I just don't think it's the right time for me to do that. With Walter Egan and John Stewed, it just seemed

like the right thing to do at those particular times. I'm real good at editing out this section, or

saying," Let's do this in here." That's the thing I'm probably best at -- being able to think abstractly

and say, "This isn't making it here; let's do this; put this part in here, and it'll make all the difference in the world." But

choosing to do that as a whole project is something that I don't do very often. On Bombs Away Dream Babies, I wasn't in the studio with John as much as I would have liked to have been,

because we were working on Tusk at the time. It kind of blew John's mind when I first met him, because I knew all his songs.

I had almost all of the old Kingston Trio albums -- although very few people will admit that these days. Steve Stills, I'm sure

he had them all, too, but he wouldn't admit it [laughs].

MUSICIAN: Usually the lead guitarist is one of the most visible members of any band, but in your case, even with

Fleetwood's phenomenal popularity, your guitar playing seems to be very underrated, if not overlooked entirely.

BUCKINGHAM: It's like being an actor and being good enough at it so that no one realizes you're acting. A bad

actor is someone who looks like he's acting, and he's ranting and raving up there. I mean, a part that you're not aware of so

much, that's a supportive and integral part of the song is a lot harder to come by, I think, than a part that you must be aware

of that's so aware of itself.

MUSICIAN: Do you have any specific influences as far as playing lead guitar?

BUCKINGHAM: I can't really think of any. See, I never played "lead," per

se. I started playing guitar when I was seven years old, and I played rhythm, chords to the old rock 'n' roll songs.

Then I got into fingerpicking, and I was very good at melodic fingerpicking. But I never played lead until 1971, because

when t was in Fritz I played bass. And the reason I played bass was because I couldn't go whoo-whoo at all. I couldn't play

screaming lead. When I later started playing lead I was probably listening, oddly enough, to Peter Green, and then Clapton

arid some of those people -- to cop the white blues licks. But that's about as deep as it goes -- which isn't all that deep. I've

always played lead begrudgingly, I'd say. ]here's not that much lead on the Tusk album, for that same reason. There's

almost an underplaying of lead, to make people think, "Where's the leads?" I was just more interested in colors on

that album. I'm getting better at it, though;. there's some pretty decent leads on the live album.

MUSICIAN: Do you practice the guitar much these days?

BUCKINGHAM: From time to time. Probably not as much as I should. But I'll start to and then I'll think, what for? It's just a

question Of what direction you want to go, and right now I'd rather put more energy into trying to understand how to write

better. So much of the playing comes out of just being in a state of mind where you're not conscious of what you're doing

-- it just comes out anyway. I'd never sit around and just try to play scales, t don't think. I probably should [laughs] --

sometimes on stage I wish I had. I do a lot of thinking about the

guitar, just in my head.

MUSICIAN: Your stage demeanor has changed tremendously in the past five

years. The guy with the pheasant shirt and the beard and the curly hair of a few

years ago hardly seems like the same person as the one on the Tusk tour, with

the gray suit' and short hair and the demonic stare fixed at the audience. Did

that change come about as the result of any groups you'd seen or listened to?

BUCKINGHAM: No, absolutely not. I'm not even aware most times of what I'm doing when I'm up there doing that.

MUSICIAN: But what about the change of appearance?

BUCKINGHAM: Well, I decided to cut my hair long before everyone else did. It wasn't necessarily to look punk or anything. I was just tired of the beard, so I shaved it. Then the hair didn't look right without the beard, so I cut it. It's all been gradual. Found a couple of new clothes stores, started buying some new suits... As far as the movements, it's funny, because I used to do more of that when I was playing bass in Fritz. I think maybe when I first joined the band, it was such a new thing, and I wasn't sure of my role. I just sort of withdrew into the back. It's not something that wasn't, there before, as far as the stage presence; it just wasn't coming out for a long time. It was sort of beaten back. I guess.

Lindsey Buckingham's Equipment

Lindsey Buckingham is currently using a Turner electric guitar. "I've got four Turners -- two 6-strings, so I'll have a

backup onstage in case I break a string; one with two pickups; and a new model that's got a two-octave neck. It's

got a boost and a couple of parametric equalizers on it, and that's about it. It's a fairly simple guitar, which is nice --

doesn't have too many gadgets. Rick [Turner] always made John's basses, when he worked at Alembic, so he

was always trying to sell me Alembics on the road, but I never liked them because they were very sterile sounding

and didn't feel very good. During the first few months of recording Tusk, Rick showed me a blueprint of this new

guitar; he said, 'I'm trying to make it more mellow-sounding, warmer sounding -- sort of a

combination Les Paul and Alembic.'"

Buckingham uses flatwound strings on the Turner to, as

he puts it, "get more of the note and less of the overtone. It's a little less 'wire' sounding."

He is now using MESA / Boogie amps through HiWatt cabinets, and his only effects are a fuzztone and an echo

unit. ("I'm not sure of the brands," he admits, "Raymond [Lindsay], my guitar roadie, takes care of all that.")

For acoustic numbers, Buckingham ordinarily uses either Ovations or a Japanese Tama with a pickup in the

soundhole.