WAITING ON THE COUNTDOWN... No grand critical proclamations here. Only the truth: Lindsey Buckingham is set to release Out of the Cradle, the pop album of the year —perhaps the pop album of the decade on June 16th. You can safely call it "America's Great Pop Hope," and not feel at all silly doing so.

The album borrows its title from "Out of the Cradle, Endlessly Rocking," Walt Whitman's 19th century poetic ode to childhood innocence and it doesn't take a literary scholar to see that the title (and the connection) works on many different levels. There's an innocent quality to much of Out of the Cradle, and this goes back to the whole pop music philosophy and tradition. It's a tradition that dates back to the earliest days of rock 'n' roll, straight through Pet Sounds, and right up to any number of tunes that you can remember sounding great as they blasted from an AM radio throughout the mid-'70s

"There is an innocent quality to it," says the 42-year-old Buckingham. "Walt Whitman meant that title as the child that stays within the man as he's walking around as an adult, and the child that's still in there rocking. So that definitely appealed to me. Even the packaging has an innocent quality. It's al-most bordering on precious," he laughs, "but I've got old family photos in there and all that, and the whole thing has kind of a Remember this?' sense to it. The songs aren't necessarily about the band [yes, he means that band] or about anything, really. But maybe they're about just trying to take a period of time and trying to put it into the healthiest possible perspective you can.

In 1982, by which time the band he refers to had

turned into the "enemy" in the eyes of many rock 'n'

roll fans, Lindsey Buckingham wrote and recorded a

little pop-rock ditty called "Oh, Diane," which turned

up on side two of an album called Mirage. The song

was so innocent that it bordered on the ridiculous,

although its magical, four-chord musical structure

never fails to bring up emotions associated with

everything from doo-wop to Buddy Holly (and, by

connection, the whole British and American pop-

rock explosion of the mid-'60s).

Of course, you could also add Brian Wilson to that

chemistry, thanks t a pristine-sounding, modern

production; spacey backup vocals; a mandolin and /

or harpsichord (you can't quite tell), which might

sound out of place on paper and in concept; and

several instrumental bridges that come out of leftfield.

The song went on to become a big hit in England. At least one person even in his now-jaded,mid-30s still suddenly latches o n to all his hopes,

dreams, and desires; remembers there are beautiful

things in this world; and wants to run out and really

fall in love, each and every time he hears "Oh, Diane."

All in the course of a 21/2-minute pop tune! Which,

of course, is exactly what Jonathan Richman had in

mind when he sang about "the power of the AM..."

Or the power of pop. Which is sort of a long way of

describing what the power of Out of the Cradle is all

about.

SOUL DRIFTER

Not that each song on the new album is like "Oh,

Diane" — although they're all just as evocative. Still, it

probably needs to be explained in this age of Wilson

Nelson and Mariah Bolton that "pop" music is not

necessarily synonymous with "easy-listening" or

"MOR." It's probably closer to what they call "Classic

Rock" these days. Buckingham's roots run incredibly

deep, but the first taste of Out of the Cradle you've

probably heard is "Wrong," a wailing, dark view of

classic rock stardom and the "biz," which was sent to

AOR radio the middle of last month. In fact, the

album is chock-full of incredible, gritty guitar solos,

with its share of hard rockers. On the other side of the coin, however, are beautiful tunes that approach the mainstream, while straddling the esoteric. Songs like "Soul Drifter," "You Do or You Don't," "Surrender the Rain," and "Turn It On" wouldn't sound out of place on any radio format.

There's a Buckingham reinterpretation of the old folk

song/spiritual, "All My Sorrows," which approaches

Beach Boys' territory, circa "Wind Chimes" or "Surf's

Up." There's "Countdown," an anthem of hope, the

single in Britain, and the cut that may lead the pack

if only by a hair. It's one of those songs you feel you've

heard a thousand times before in your dreams the

very first time you hear it; that is, love at first listen.

There are several thrilling, unpretentious, classical

guitar interludes. The esoteric bent-including the

opening "Don't Look Down" (yet another ode to hope, and the one Buckingham preferred to be the first single) - surely should appeal to an "alternative" audience. You could safely say that Out of the Cradle has the potential to become a commercial monster, and not feel at all silly doing so. Hell, it's hard to say where the audience for this one even begins...or ends, for that matter. After all, "You Do or You Don't" actually quotes a melodic line from "A Theme From A Summer Place." ("I always loved that song," recalls Buckingham. "It always takes me right back to 1960, and it just seemed to have the same emotional tone I was looking for') — while the final song on the album opens with an acoustic guitar interpretation of Rodgers & Hammerstein's "This Nearly Was Mine" from South Pacific. All of which just goes to demonstrate how deep Buckingham's roots are as a master musical craftsman.

"I don't know if you'd call them roots. But that was some of the first stuff I heard, because in the early '50s, before Elvis hit, that's exactly what parents were listening to. But those songs really were great, and they hold up so well. Writers like Rodgers & Hammerstein and George Gershwin really knew what they were doing. And really, when you get down to it, the Beatles, and maybe just a few other artists from that time, were the exception of someone who could d o something on that level without having to train to do it. Everyone since then has tried to pull that off, but it's really hard to do without musical training and knowledge. I mean, I can't even write or read music, so I really don't know. But I do think there's a lot to be looked at in that type of music. I tried to get that traditional, Tin Pan Alley sort of approach when I was writing 'Soul Drifter, so I think there's a lot of validity, just looking at that stuff and appreciating it. Especially if it's part of your background."

THIS IS THE TIME

You could call Out of the Cradle Lindsey Buckingham's songwriter, and the producer on each of his albums, sharing the latter credit (as well as an occasional songwriter-nod) with his longterm friend, Richard Dashut.

"Richard's not a musician, per se, or really an

engineer in the finer sense of the word," he says of the

mystery man behind the scenes. "Neither one of us is

that technically oriented. I'm just blessed with a fairly

decent imagination, I guess, but that probably comes

from years of listening to hits. It gives you a sensibility

about how something could become that much more

accessible, o r at least that much more effective. Our

philosophy has always been, turn the knobs until it

sounds good.

"Stevie and I moved to Los Angeles in, probably

1973, and we met him almost immediately. He was at

another studio, and then he moved over to Sound

City in Van Nuys, where Stevie and I recorded the

Buckingham Nicks album, and he second-engineered

that album. By that time, the three of us were all

sharing a big apartment together, and he just contin-

ued to work with us. And when we were asked to join

the band, I just said, 'Hey Rich, wanna come out on

the road and mix sound?'"

Of course, the last two albums by that other band —

Mirage and Tango in the Night-were pretty much

produced by this same team; in fact, the story goes

that Buckingham's last solo effort was scratched in

1987 so that he and Dashutt could go into the studio

to "save" Tango in the Night. Which probably explains

why it was the first album by that band on which the

duo got sole production credit, if not why the album

was the final release by that group to reach the top of

the charts and produce a slew of hit singles.

What makes Out of the Cradle his first real solo

release, however, is that in the past, he always felt

obliged to give his rockers to that other band. And

since the band was obviously as close to mainstream

rock as mainstream gets, he driven to immerse himself

in the experimental side on those earlier solo releases.

After all, that same experimental side failed miserably

on relative commercial terms when he

incorporated it into the band on 1979's Tusk. As a

result, Go Insane was downright weird, including

stuff like a bizarre musicial suite dedicated to late

Beach Boy drummer Dennis Wilson.

"I knew him pretty well — he even had an affair

with my girlfriend," he laughs. "But he was a good

guy. He was kind of lost, but I thought he had a big

heart. I always liked him. He was crazy, just like a lot

of other people, but he had a really big heart, and he

was the closest thing to Brian [Wilson] there was, too.

He was halfway there.

"That was a bit of a darker period," he admits. "I

think Law and Order was more like a Lindsey

Buckingham variety show. But with Go Insane, there

were a lot of not-so-great things happening in my

personal life and I really felt I had been drifting a little

bit creatively. The band was getting crazy, and personal

things were kind of crazed, and that was the

product of a very stressful time. I remember I was

back East, and some girl called me up, and said, Why

do you have to write about such down stuff?' Because

that's what was happening."

With Out of the Cradle, however, Buckingham has

had a chance to merge all his diverse pop sides and

influences into something that's totally cohesive,

"After I left the group situation, I just kind of sat,

tinkering around, letting the emotional dust settle,

and.then I started getting into it. It's time consuming

when you're doing everything yourself, but I just felt

I wanted to get some of the instincts back, and some

of the things that I maybe put aside a little bit with the

band-things that sort of got left by the wayside, like

different guitar styles.

"I do have this little esoteric niche that helps in

terms of how you're perceived, as well as giving you

sort of a whole area to tinker around in and maybe

grow. But then I also had that mainstream thing to fall

back on. I really thought it was important to cover all

the ground of what I'm about, and not just keep

cultivating the little sidebar there. I mean, I really

wanted to get away from too much synth, and really

assert the guitar playing a little more, even to the

point of being a little flashy. So, I just tried to get it all

in there, as much as I could.

"And I did think that if I were to continue as a solo

artist and have any sort of longevity, it would probably

make sense to approach it this way... but to do it

without becoming something you didn't want to

become in the process. Which is a really fine line, you

know?" What would be something he didn't want to

become? "Just gearing your entire approach to what's

going to sell. Besides, God only knows what's going

to sell; that's part of the problem these days. I mean,

15 minutes is really becoming 15 minutes. When

Bruce can come out with two albums, and they can hit

the top immediately, and then go down just as fast.

This is why he did Saturday Night Live, right? I mean,

that's a scary thought. So God knows what my album

is going to be perceived as. Also, you don't want to

water it down to be more radio friendly. And you still

want to make it somewhat challenging - make it your

own and make it fresh. So if you can do all that, and

still make it accessible, then I guess you're doing

alright."

STREET OF DREAMS

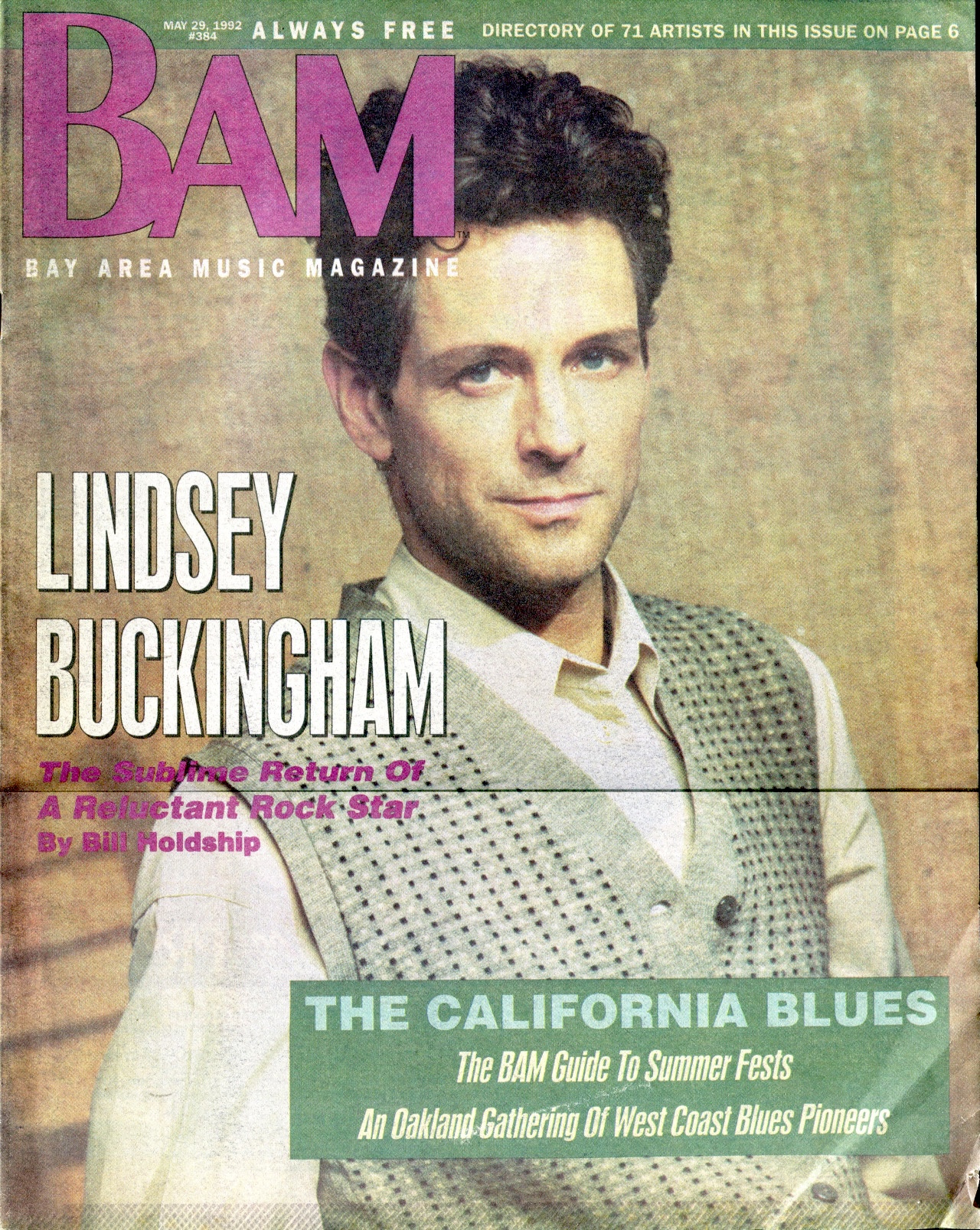

The first thing you may notice about Lindsey

Buckingham is how "normal" he seems to be for a

rock star. This may be your thought, regardless of

whether he's sitting in a Warner Bros. conference

room in 1992, following five days of "video hell" with

director Julian Temple; or in his own Bel Air home

studio dubbed "The Slope" back in 1987, feeling

somewhat miserable and trapped (and perhaps not

unlike Michael Jackson at the time of the Victory tour)

because that other band needs him to go out on tour.

(The band's namesake drummer, in fact, made no

secret of the fact that he's broke.)

Perhaps the normalcy has to do with his fairly

traditional upbringing in a small Northern California

town called Atherton, near Palo Alto. Growing up in

a middle class family (his father owned a small coffee

company), Buckingham makes it sound almost like

an episode of The Adventures of Ozzy & Harriet, with

him in the Ricky Nelson role.

"I had a swell childhood - two older brothers, great parents,

and lots of activities and shared quality

times," he recalls. "And it was one of the older brothers

who was probably responsible for me doing what

I'm doing, in the sense that he was old enough to be

buying the Elvis records in '56 when I was only 6. He

was the one who collected all the great 45s — he still

has them — and I used to just sit in his room and listen

to those things over and over again.

"Of course, that wasn't an uncommon story in the

'50s. I'm sure if you asked Bruce what he listened to

growing up, it would be a similar situation. I mean,

anyone can see how strong that image of a guy with

a guitar was. And all of us, even at that age, could hear

the difference between 'How Much Is That Doggie in

the Window' and Heartbreak Hotel, and see what a

jump that was. Yeah, a lot of kids running out and

getting guitars in 1957 and '58, I'm sure. And I was

one of them. I started very, very young. No lessons,

just playing and listening to the records.

"By the time Hendrix came along, he didn't have

much of an effect on me. I mean, I enjoyed what he

was doing, but I cut my teeth on [Elvis's lead guitarist]

Scotty Moore, so that by the time Brian Jones and

Keith Richards came along, I wasn't overly impressed

by what they were doing as guitarists. I mean, I loved

how they made their records. Obviously, I love that

stuff, but it wasn't like I was going, Wow, listen to

that guy!' I mean, I could already play. When the

psychedelic stuff came along, I wasn't taking

drugs...quite yet," he laughs, "so I would go up to the

Fillmore and watch all that stuff, but I was so locked

into my style as a guitar player that it didn't really

influence me much.

"Plus, right about that time, I switched over to play

bass [in the Bay Area band, Fritz]. It was actually the

first band I was in, and I switched to bass because I

didn't have a fuzz unit. In fact, all l actually had up to

that point was an acoustic guitar. Thad started playing

young, but I had always kept it to myself. I mean,

I was a swimmer in high school, and our family was

very athletic. My mother was never one to say, Yeah,

you should go into entertainment, because she knew

what a rough life it was. So she always encouraged

me to be a good player, but never as a career. And

then, right after high school, someone saw how well

I played, and they just sort of yanked me out of my

situation. That same fall, I quit the water polo team,

grew my hair out, and that was it. My mom was

going, 'Oh my God!' My brother's going, You're not

going to let him grow his hair out, are you?!'

"Fritz did OK in the Bay Area. We opened shows at

the Fillmore maybe once or twice, but it was not a big

thing. At some point, however, Stevie and I kinda got

selected out of that group as the ones who were

perceived as having the most potential. We had not

gotten romantically involved until that time, though,

and when Fritz broke up, we kind of got together on

a lot of different levels. We met [producer] Keith

Olsen, who eventually brought us down here to LA to

make the Buckingham Nicks album, and one thing led

to another. It was kind of a tough time, actually. After

the album went down the toilet, we had managers

who were trying to get us to play steakhouses and

that sort of stuff... which we figured was a dead end

so we didn't want to do that. We also had to deal with

a record company that didn't seem to have any idea

of what the music on the album was about.

"So, yeah, we had to deal with all that. To make

money, I had to go out on the road with Don Everly's

band. Which was as heartbreaking as hell, watching

Don trying to do something that wasn't being

received very well. Stevie was working in LA as a

waitress. And yet this whole cult thing was emerging

out of the South, where we were able to headline in

front of 5000 people. I mean, that was just a bizarre

contrast to what we were dealing with in Los Angeles,

where we were starving. We weren't much a part

of the scene in LA during the early '70s. We played the

Starwood and a few other clubs, but not in a situation

of prestige at all. One time, I was right in the middle

of a song, and the club manager walked up onstage

and turned down my amp. We had to deal with all

that sort of stuff. But we went down south and

opened for Poco, and they absolutely loved us. We

never really found out what would've happened

with that scene, because right about that time, Mick

[Fleetwood] stepped in and asked us to join. We

thought about it for a week, and then we went, 'Oh,

OK. Let's do it.'

"They weren't making any money at all. Fortunately

they were on Warner Bros., which has always

been an artist's label. And Mo [Ostin] had seen them

through all these various incarnations and still

believed in what they had going. And Mick was defiant

in terms of seeing something through, believing in

what he had to offer, and what certain aspects of that

band had to offer."

"HEY, MR. ROCKCOCK, WHERE DO YOU BELONG...? "

"I think that Fleetwood Mac's success probably did

hurt the work after a while. After Rumours which

was a mega, mega, Michael Jackson of its time kind of

thing — the music was secondary to the phenomenon

itself. It's kind of a dangerous position for an artist to

be in, at least as far as keeping yourself honest. So my

reaction to that at the time was to say, 'OK, I'm going

to work in my house for a while with one mic and

nothing else. My stuff that ended up on Tusk was

kind of a reaction to all that. I didn't want to make

Rumours II or be put in the position of repeating

ourselves for the wrong reasons. I was probably

overreacting a little bit, you know, but in retrospect,

I'm glad we did it. But from that point on, I think the

work did start to suffer a little bit. There was a certain

wind taken out of all our sails, and I think you can also

add personal stories to that one. Stevie was getting

more and more drawn into her own things, and I

think the moment and the unity that the group had -

which was from the first album through Rumours -

started to just dwindle. And I'm sure that did have an

effect on the work as a whole.

"But Tusk was sort of liberating, because I saw this

whole machine gearing up for Rumours II, and I saw

people frothing at the mouth for what I perceived to

be all the wrong reasons. And I saw the record company,

to some degree, expecting us to... You know,

I tend to say these things, and then I think, Well, gee,

Lenny [Waronker's] going to see this in print, and it's

not a nice thing to say about the company, but...""

Buckingham is reminded that, in 1987, he recalled

delivering Tusk to the label, and someone then telling

him that everyone sat there watching their Christmas

bonus check flying out the window. He laughs. "I

shouldn't say stuff like that. But I did see the machine

gearing up, and I saw the whole focus not being on the

music, but on this musical soap opera, if you will. Of

course, right around the same time, a lot of new music

started coming out of both England and America. It

wasn't an influence so much as it was a validation of

the sense that it was OK to maybe look into some

other things that had very little to do with what Rumours

was all about.

"So, personally, I didn't feel hampered by Fleetwood

Mac at that time, because I'd go home, and tinker

around in the bathroom with a mic on the floor, and

I'd be banging Kleenex boxes, and that was very

liberating for me. It was only afterwards - when it

became clear that there was either a little bit of a

backlash, or maybe I'd just overestimated what the

public wants to hear. And that's when it started for

me. I was sort of left not knowing exactly what course

to chart. I was kind of drifting through a mirage, and

it was pretty much like that until the end with me.

"And, of course, by that point, everybody in the

band had their own manager." He laughs. "Which

was pretty funny. It really got to be comical.

Sometimes I'm surprised it lasted as long as it did with a

group like that. Compare it to someone like the Buffalo

Springfield, where you have just so many distinct

forces going on that it can't last. And there are times

I wonder what would have happened if, say, Stevie

and I had continued on whatever path we were on,

with that little cult thing going on down south.

Joining Fleetwood Mac wasn't really a clear-cut choice for

me. I remember saying to Stevie, when we had

finished that first Fleetwood Mac album, 'God, this sounds

kind of soft, doesn't it?' And she's going, 'Oh, no, it's

going to be great!' She was right, but it still was

something I was a little more ambivalent about all the

way through. I think Stevie's tendencies were more

toward that softer thing, anyway. But I decided to go

with it and to see what would happen — and,

suddenly, we're the biggest band in the world. How do

you reconcile that with what you might feel or your

own doubts about the completeness of the situation?

You don't. You just sorta just go along with it. And

you say, 'OK, here I am. I have a very clear cut role in

this band, aside from being a writer and guitar player.

I'm the one who takes this stuff and fashions it into records.

"There was a lot of dependence on what I was

doing at the time, both in the studio and the touring.

It got to be very repetitive, and of course, the whole

lifestyle on the road just got to be more and more

decadent in many ways. Not just in terms of habits or

anything, but the huge jets and spending way more

money than we needed to spend, and all that. It was

the classic kind of rock thing. That went along with

the whole Rumours vibe, though. It was the machine. It's geard up.

This is what we are, so..' Unfortunately,

it doesn't really reinforce the work ethic very

much, or the sense that if you're any good, you can be

better. Or that you should be working solely for the

work, and trying to improve what you're doing,

rather than for the perks and all that. So it was a very

complex situation. But I have no complaints. I wouldn't

have missed it. But you do find yourself in situations

that maybe weren't that ideal.

"I think that Stevie's selection by the masses as the

focal point was the first thing that became known. I

think slowly it became understood what my contribution

was behind the scenes, and that seemed to

manifest itself in the press, and even the way I was

presenting myself onstage later on. But you have to

remember, there was also a very unhealthy emotional

situation going on between two couples who had

broken up, and were trying to say, 'OK, we don't

want to see each other, but we're going to have to do

this anyway. You stay way over there, and I'll stay

way over here. So it was kind of a mess from the

beginning, at least emotionally. I think that

professional jealousies were probably actually less of a

problem than just the inherent dynamics between

two ex-couples. Which never really went away. I

mean, Rumours truly was the musical soap opera on

vinyl."

GO YOUR OWN WAY

"Knowing Mick and how many incarnations he'd

been through, there was no doubt in my mind that

they'd go on without me. So I guess you could say in

a way that I was let go when they decided to do that

last tour." He laughs. "Whether of not I would have

done another album, I don't know. I initially had

thought about leaving after Tusk. I don't think it

would have been a good idea, because it was important

to do it at a time that was not just good for

yourself, but maybe wasn't going to be too hurtful to

everybody else involved. After Tango in the Night, I

thought, Well, OK, I've done the album. If I don't

tour, it's not going to be a huge blow to them, if you

want to think of it karmically or whatever

"I didn't see the last tour. The only thing I saw

was... in fact I didn't see that, either! During the last

two shows in San Francisco and LA, I got up and did

'Go Your Own Way' with them. Which was a lot of

fun. It's easy to look good in that situation - coming

in and doing one song that you know really well, and

know you can do better than whoever's been doing it.

So there's no way that could have been anything but

a positive experience for me. It was also just a totally

nostalgic thing to do. Even then, though, I didn't

actually go out and watch the show." He laughs. "I

didn't want to. I don't know why. So I can't comment

on what they were like without me."

And then there was Mick Fleetwood's "tell-all"

autobiography, which kind of transferred the band

into something out of the pages of a national tabloid.

"I skimmed Mick's book," he says. "I found there

were a few things in there that weren't accurate.

Everyone was very hurt by that. Not by any facts in

particular, which I definitely was hurt by, but just the

tone of it in general. Just the fact that it was so trashy.

Fleetwood Mac may have wound down, but it's a

shame to have things come out that sort of add a lack

of dignity to it. It doesn't have to be that way. I was

very unhappy with a couple of very specific incidents

described in there, which were totally untrue. I never

responded to it. I didn't think there was any reason to

dignify it. But there was one story that had me

slapping Stevie when I said I was leaving the band. The

next time I saw Stevie after that, she came up to me,

and said, 'God, I'm really sorry he wrote that.' She

was apologizing to me for something he wrote... So,

I don't know. I think that was the product of a lot of

late nights Mick spent with a writer, and maybe not

keeping as much control over what was said, or

certainly what was edited, as should have been. I

really don't know. I'm fairly sure that he's sorry he

did that. It was unfortunate. But, once again...that's

show biz!" He laughs.

"But they're going to put together a 25-year

Fleetwood Mac retrospective, which will probably be

out at Christmas. They want to put a couple of new

tracks on it, so I'll probably do one and produce it for

them. There's no reason not to. I don't really see

anyone very much. But it's not like there's any hard

feelings involved. I think there may have been some

from their end when I first left the group, and they

were going, Yeah, we don't need him!' and all of that

But now things have just kind of wound down all

around..."

EITHER YOU DO OR YOU DON'T

There's one final element in that long chain of pop

music, a la Holly, Wilson, Lennon & McCartney, and

Buckingham, that we've been talking about through -

out this article, and that's the element of integrity - be

it being true to yourself and your art; or discussing

how the darkest song on Out of the Cradle, "This Is the

Time," could be seen as a cynical political statement,

and then reflecting, "It's terrible right now, you know.

People are thinking, How can we exploit the riots?'";

or mentioning that a specific song on the album is

about a family tragedy (no, it isn't "Street of Dreams,"

which has a line about his "daddy's grave" in it), and

then quickly adding, "But that's off the record—I

don't want to exploit that, either"; or simply refusing

to go on the road with your old band because you

realize it's being done for no other reason than to

make money. And lots of money at that

"The irony is that I really want to get back together

with musicians now, and get back on the road,"

claims Buckingham, who, in 1987, said his desire was

to put together a stage show that fell somewhere

between Frank Sinatra and Laurie Anderson." I'd

especially love to find a bass player and a drummer

with whom I could create a core to develop the guitar

sound — almost in a jazz way, but not necessarily

with a jazz sound. It seems to me that I should really

just go out and play - not as a mechanism to support

the record, but just because it seems like the other side

of the coin in terms of growing as a musician and

getting out of the garage." He laughs. "I've been in

my garage for four years! I have no idea of whether I'll

play clubs or small theaters. Everyone is a little

pessimistic about that. But there may be a whole grassroots

sort of audience out there that's invisible to agents

and managers and people who would assume you

can only play small places. But I will play anywhere.

It's a must. It's part of a survival move, just like

leaving Fleetwood Mac was."

Finally, Buckingham reflects on what some people

have termed "disposable California pop," even though

it's a sound that counts art as wonderful as the Beach

Boys, the Byrds, and even the Mamas & the Papas

among its cultural antecedents. "Obviously, there's

going to be some sort of a backlash against a band that

was as popular as Fleetwood Mac was," he

concludes. "I think part of the reason Fleetwood Mac got

some flak was because we were so popular in 1977. I

mean, the biggest band in the world, and we probably

sold more albums than anyone ever sold, and all of

that. And it was a real thing. If you listen to that

album, it's not bad. There's a lot of great playing on

there and stuff. Tusk is still my favorite thing. But

because of our visibility, we were always a target for

criticism. I can't feel bad about any of that. I mean, I'm

doing what I do. I've always felt that, on some level,

I was trying to create a niche that was somewhat

outside of that target. But beyond that, there's

nothing that I can do. I am what I am, and you're always

going to find somebody trying to knock you down.

"Again, I think Fleetwood Mac as an entity would

get more of that than I would, personally. But it's

inevitable, yeah. I've lived in California my whole

life, so... About a year and a half ago, when there

were only a few songs mixed for the album, I listened

to it, and I said to Richard, Well, it sounds very

California. I looked at him, and he said, But I guess

you wouldn't want it to sound like The Cure. No, I

don't think so.' So what are you going to do? Within

that framework, I've still created some kind of a

sound that's mine. What else can you do?"

by Bill Holdship

May 29, 1992

read the scanned pages of the article here